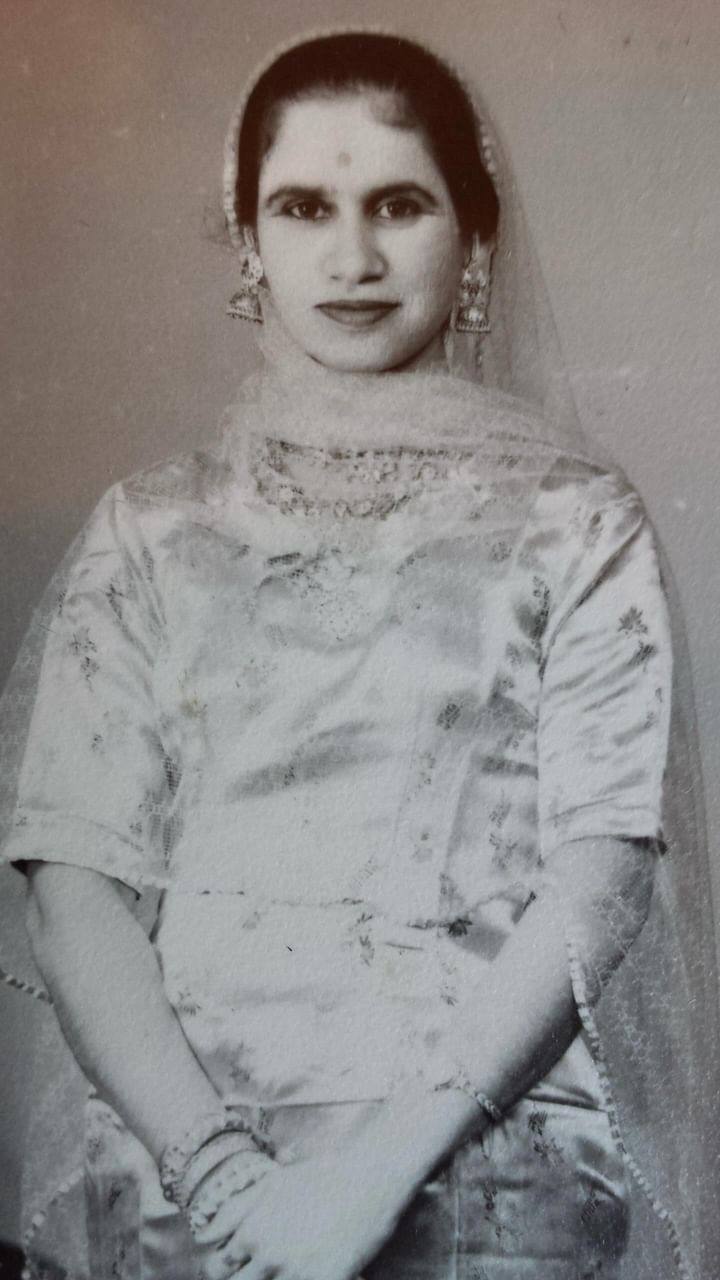

Born in 1918 in Calcutta (Kolkata) into a large Jewish community, her mother was from Singapore and her father hailed from the Middle East. Jewish people had been contributing to the city’s economy and culture for centuries, with businesses established in various sectors such as banking, manufacturing, retail and trade. The Manasseh family business imported and exported jute, with the Calcutta branch run by her father.

While still very young, Sylvia was sent to boarding school in England along with her brother. “He went to Cheltenham and my mother wanted me to go to Cheltenham, but I had a cousin in a school in Eastbourne, and she persuaded my mother to send me there.”

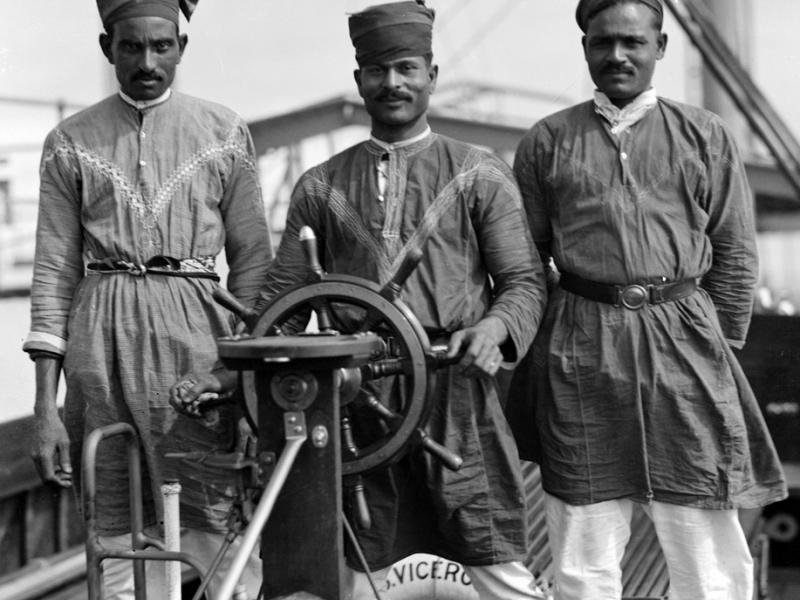

In 1939 Sylvia was in India visiting family when war was declared and because of travel restrictions she remained in India. She joined the Women’s Auxiliary Corps, or WAC (I), on its creation in 1942. Along with the Medical Service Corps, this was the first time women had entered the Indian Armed Forces. Around 11,500 women served in a huge range of capacities, from clerical work and switchboards to driving and anti-aircraft direction finding.

“When I started, my first job was in the anti-aircraft brigade working for a brigadier.” Much to the envy of her peers, Sylvia was given command of a jeep to get her from her home to the base; “the other girls were very jealous…”

Sylvia’s godmother, Rachel Ezra, a notable figure in Calcutta’s Jewish community, began helping refugees. Jewish people were escaping Europe and travelling to India and the Far East for safety, and in Calcutta Rachel Ezra would meet refugees from the ships and try to find work and accommodation for them.

Rachel Ezra also contributed to the WAC (I)’s war effort as Sylvia explains: “my godmother, who had a big garden, she used to lend her garden and we used to be drilled there!”

At this time in 1943, Japanese forces were bombing Calcutta, and Sylvia’s cool demeanour was recognised. She recalls: “We could hear the planes coming over, and there were sirens, and most of the girls hid under tables. But because I didn’t, I was promoted… It was not safe to stay in a street because they used to bomb and machine gun people they saw moving.”

Junior Commander Manasseh was posted to a station in Ranchi, 250 miles from Calcutta. “I was sent to a sort of country station where they were having court martials, and I took notes. There was a hotel where I’d been to before with my parents, so I knew the place.”

Later, Sylvia was posted to Fort William, in Central Calcutta, to work under Geneal Lane as his personal assistant. She reviewed reports and compiled summaries to be sent to Delhi. Sylvia confesses to her poor spelling in taking notes and report writing. Also, as the only female officer working in the Fort, she had to have lunch with all the male officers.

Meanwhile in Britain, brother Leonard served as a pilot in the Fleet Air Arm, later becoming a renowned architect and Royal Academician.

Occasional evenings of glamour punctuated the war work. Sylvia recalls one evening where she was invited to a dance but, unaware that it was uniform dress only, wore a brilliant red dress. “It was one that my aunt in American had sent to me. So it was an American evening dress… All the other women were in uniform and they were furious, because everybody danced with me,” laughs Sylvia.

“I worked in the fort for a bit, and then (in 1945) I worked in the Eastern Command Intelligence Centre, which was in a private house not too far from where we lived.” It was here that she remained for the rest of the war, and beyond. Sylvia was finally demobbed at the end of 1946. Her colleagues composed a heartfelt and joyous poem to mark her departure.

After demobilisation, Sylvia returned to the UK and studied at an art school in Brighton and, on qualifying, became a teacher there. After that, she taught at a Teacher Training College in Singapore, where her parents had moved following the Partition. Here she worked with an architect to design an arts building which, at her request, included a pottery studio.

She left Singapore and returned to England in the early 1960s and became a sculptor, creating expression-filled portraits, including a bust of her brother Leonard.

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →