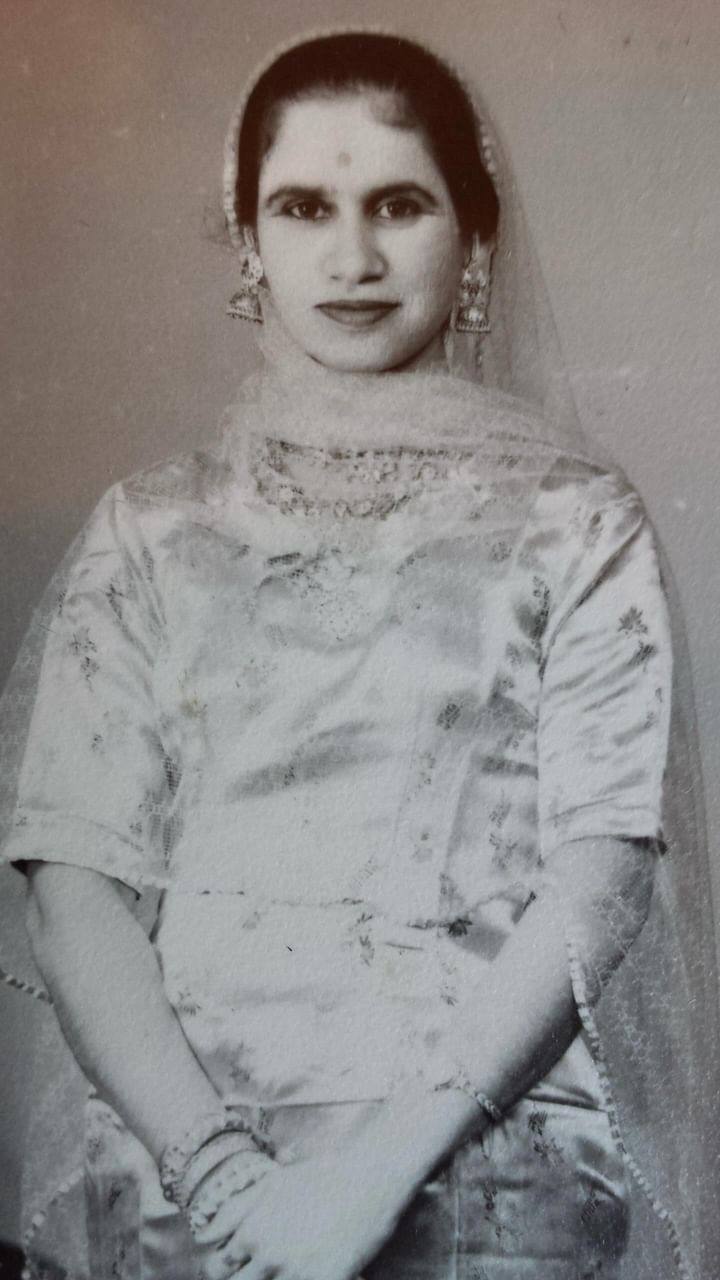

As the saying goes, “Like mother, like daughter.” In the case of creative talents, this couldn’t be more true. The influence of a mother’s creativity can leave a lasting impact on her children, shaping their own artistic endeavours and passions. In this journal I explore the profound impact my mother’s creative legacy has influenced me and how Sohavi was truly born. Roots to routes explores my late mothers life journey from birth in Kenya to India as a teenager and eventually returning to Kenya in her 20’s , to marry my father Sardar Tirlochan Singh Dhamu, to emigrate to London from Nairobi in October 1973 and live out the rest of her life. Despite experiencing loss and trauma, she endured difficulties n her younger years and made the best of her life in my fathers trusting hand, he led her to a new life in London.

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →