Born on 12th October 1921 in the princely state of Charkhari, Yavar hailed from the city of Lucknow and came from a notable background; his grandfather was the Prime Minister of the state. Exposed to the classical Urdu poetry of Meer Babar Ali Anees from an early age, a love of literature became second nature to Yavar. He graduated from Allahabad University with degrees in English and Persian Literature, with a keen intellect and a strong sense of Indian nationalism. “I was what you might call a radical Nationalist student”, he reflects. The outbreak of the Second World War, and India’s automatic inclusion, stirred strong emotions: “I was very angry! How dare they include India automatically in the war?! India should be an independent country.”

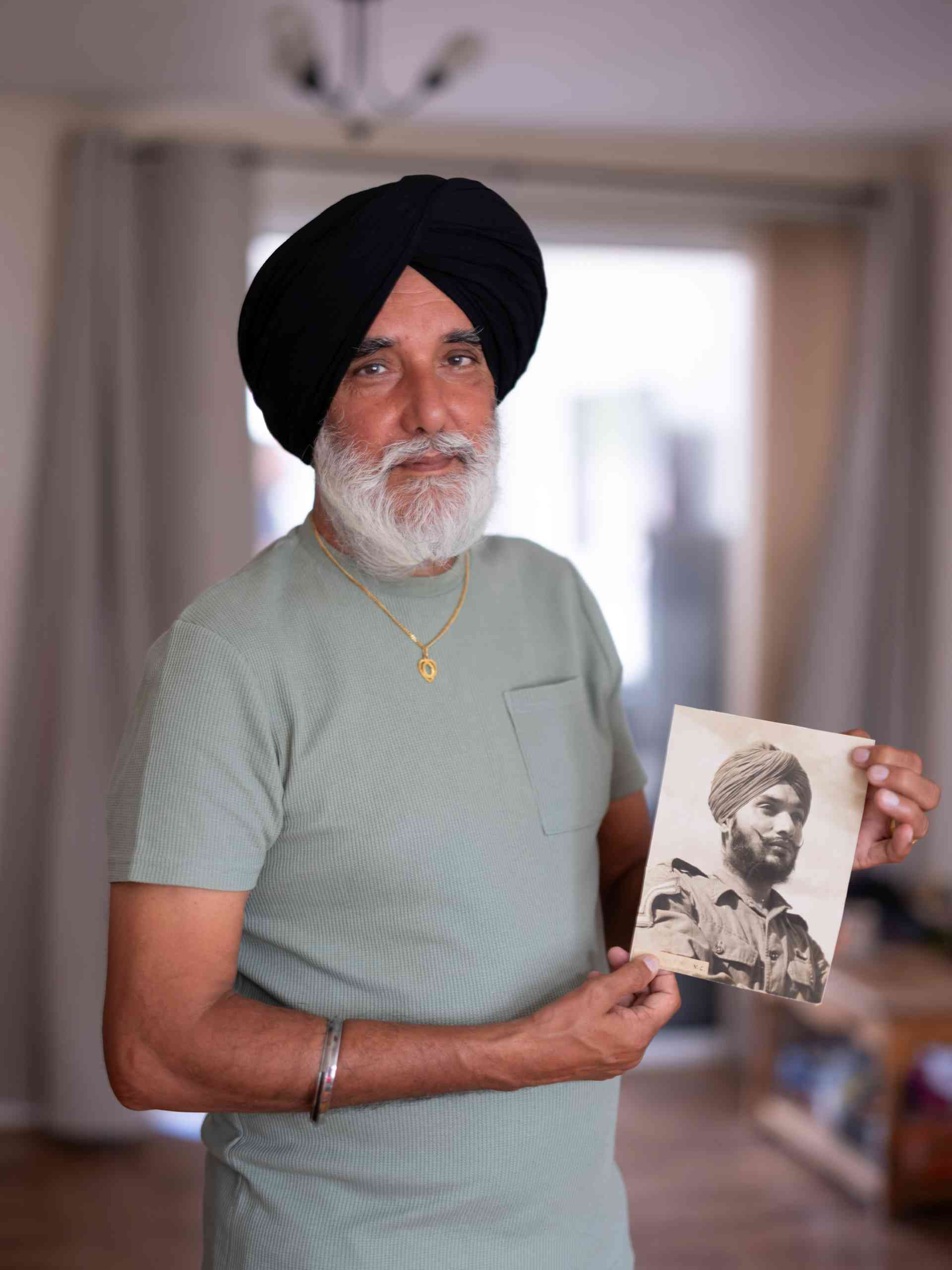

Despite these strong nationalist sentiments, the rise of fascism presented a pressing global threat. “I could see this would not push the Fascists and the Nazis out. I will make my peace with the devil, and I will join the British Army”. In April 1942, he embarked on this new route, training as an officer at the Military College, Bangalore, and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 11th Sikh Regiment. His initial posting to the 17th Battalion in a remote part of East Bengal, however, proved frustrating. “The Battalion, unknown to me, turned out to be a ‘garrison battalion.’ I felt let down. I was a 22-year-old, keen to join a fighting force. Instead, I found myself in a version of Dad’s Army”.

Life in this “god-forsaken place, called JINGERCACAGHAT” brought him into direct contact with the attitudes of the British Raj. An encounter in the Officers’ Mess highlighted the cultural and political chasms. After the Commanding Officer expressed his desire to leave “this hell hole of a country”, Lt. Abbas retorted from the junior end of the table, “You are right, Sir, that will be my happiest moment too”. This led to a period of being subjected to “a course of ‘discipline’ (best forgotten)”.

An opportunity for a different path arose through an Army Gazette advert seeking officers for training as combat cameramen. “I had been a keen amateur with an 8mm home-movie camera. I applied for the course, and the C.O. gave me a glowing report (good riddance) to ensure that I got the job, which I did”. This marked a significant turn in his journey. He found himself at the newly established Indian Army Film Institute in Calcutta (Kolkata), undergoing intensive training run by professional British filmmakers. “I was in seventh heaven”, he recalls.

Soon, Captain Abbas was on the front lines of the Burma Campaign, “armed with a pistol and a Vinten film camera”. His role gave him a unique vantage point. “I saw a hell of a lot more action at first hand as war correspondent-combat cameraman than I would have done if I had stayed as an infantry officer”. He filmed pivotal moments, including the grim aftermath of the Battles of Imphal and Kohima and the crossing of the Irrawaddy and Battle of Mandalay in early 1945. He acknowledged the risks: “I could have been shot, I was taking grave risks, but somehow I didn’t… I climbed on a tank roof once, during the fighting. The tanks behind me must have sent a signal to the tank commander of the tank on which I was sitting. Very soon the hatch opened and I was put in my place – which was on the ground!”.

His work brought him into contact with senior figures, including Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, the Commander-in-Chief, for whom he was assigned as a special cameraman. “Auk, as we fondly called him… was very fond of me… He was much older than me and used to occasionally talk to me in Urdu”. This relationship proved significant later in his career.

The end of the war did not bring an end to upheaval. The partition of India was a deeply painful period. Captain Abbas was tasked with filming the ‘Birth of Pakistan’, leading an Army convoy carrying infrastructure from Delhi to Rawalpindi. “The scenes of destitution, of hapless and helpless refugees travelling in both directions… are also seared in my memory”. His personal loyalties were tested, as his elder brother was an officer on the Indian side in Kashmir. It was Auchinleck who facilitated his disengagement from the Pakistan Army, advising him in Urdu, “Captain Abbas I think you better go to your susaraal (in-laws). He meant England”. This advice followed his meeting and falling in love with an Englishwoman, an officer in the Women’s Auxiliary Force, while posted in Japan with the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces.

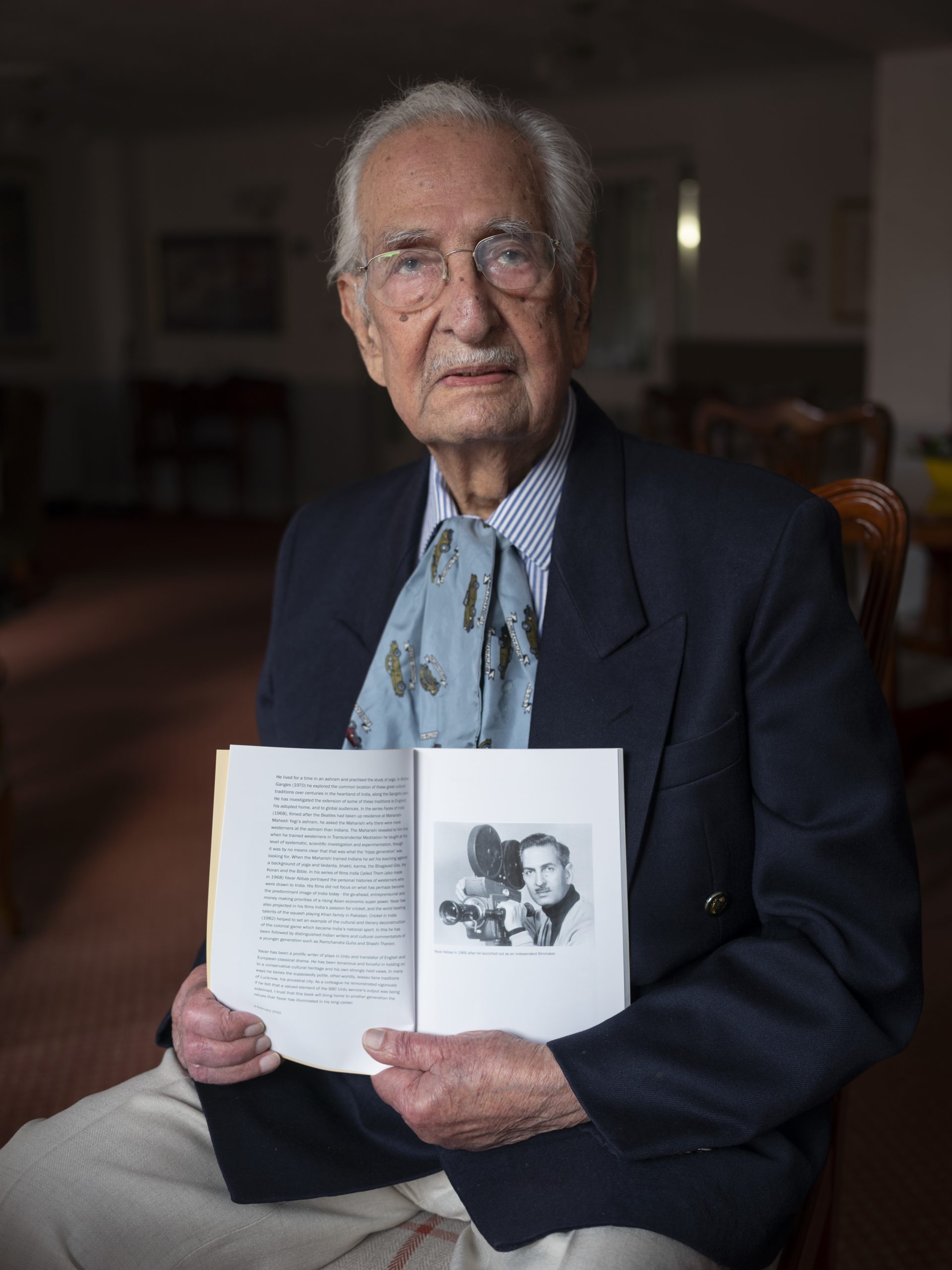

Captain Abbas eventually settled in England, establishing his own film company. His subsequent career saw him move freely between making films, broadcasting and journalism. He translated the works of literary giants like Shakespeare, Shaw and Dickens into Urdu for plays and features that he produced and directed for the BBC. His own films, including ‘India! My India!’, ‘Faces Of India’ and ‘Cricket In India’ were shown on national TV networks and won awards at international film and TV festivals. He also served as a Films Consultant to the United Nations, Chief of Films and Television at Third World Media and gained renown for his recitations of the poet Anees.

His wartime experiences profoundly shaped his worldview. “I have acquired a great respect for the soldiers but a hatred for war”. He remained a staunch advocate for peace and justice throughout his life.

Reflecting on his service, he acknowledged the complexities: “I was defending democracy and freedom and everything that is good and noble about humanity! I didn’t put it in those terms at that time, but that must have been my driving force. I was proud to be in the army. I still am proud of what I did”.

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →