Its grandiose halls, once the epitome of royal luxury and leisure, were repurposed to serve a noble cause: as a hospital for soldiers of the Indian Army.

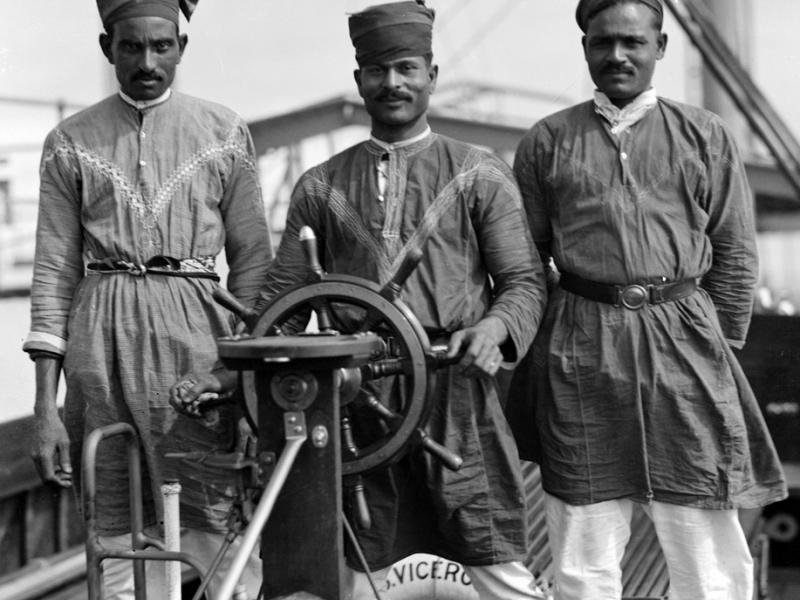

In 1914, as the First World War escalated, the British government recognised the need for extensive medical facilities to treat wounded soldiers. The Royal Pavilion was requisitioned and converted into a military hospital, specifically designated for Indian soldiers who were part of the British Indian Army. This decision was influenced by both strategic and symbolic reasons, aiming to honour the contributions of Indian troops and provide them with a semblance of familiarity in an unfamiliar land.

The Pavilion’s architecture, with its domes and minarets, was thought to offer a comforting environment reminiscent of the soldiers’ homeland. The conversion process was swift and efficient; lavish rooms were transformed into wards, the opulent Banqueting Room housed 60 beds, and the Music Room was adapted into an operating theatre.

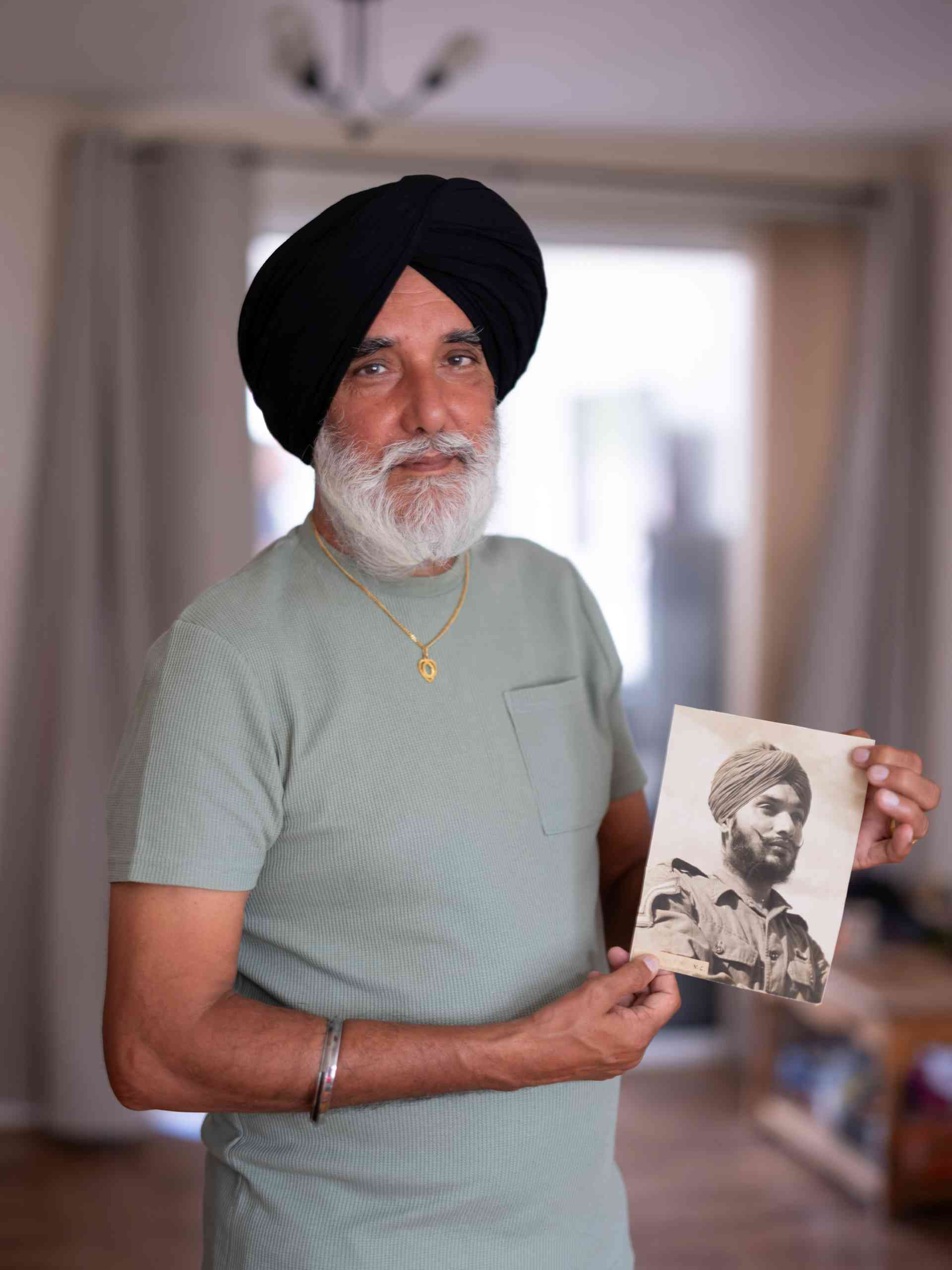

It treated thousands of soldiers, many of whom had sustained severe injuries on the battlefields of Western Europe. Among the notable soldiers who received treatment were Sepoy Khudadad Khan, the first Indian soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest military decoration for valour. His story, as narrated by Nurse Alice Fullerton Lindsay Gray, an Australian Red Cross Bluebird nurse, highlights his bravery:

Nurse Lindsay Gray writes from Brighton on 22 December 1914:

“King George asked that the Royal Pavilion and Dome should be turned into a hospital for the Indian troops. So, the Corporation of Brighton has also turned over the county schools. The pavilion was built by George IV, as a palace, but of late years used as a concert hall. It is a beautiful place, great space filled now with beds and nice grounds. Here, as a patient, and a very sick one too, they have the first Indian to receive a V.C. He bayoneted a German officer, then 10 men. After that he feigned death, was hit by a German with the butt of his rifle, but never turned a hair, and later on he and a German officer dressed each other’s wounds. He tells the tale quite simply. Nothing to make a fuss about he thinks.”

Subedar Mir Dast was another Victoria Cross recipient also treated at the Royal Pavillion. As a Jemadar in the 57th Wilde’s Rifles, he displayed remarkable bravery during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915. Despite a deadly gas attack and heavy losses, he led his platoon and rallied remaining soldiers. He also risked his life to carry wounded soldiers to safety.

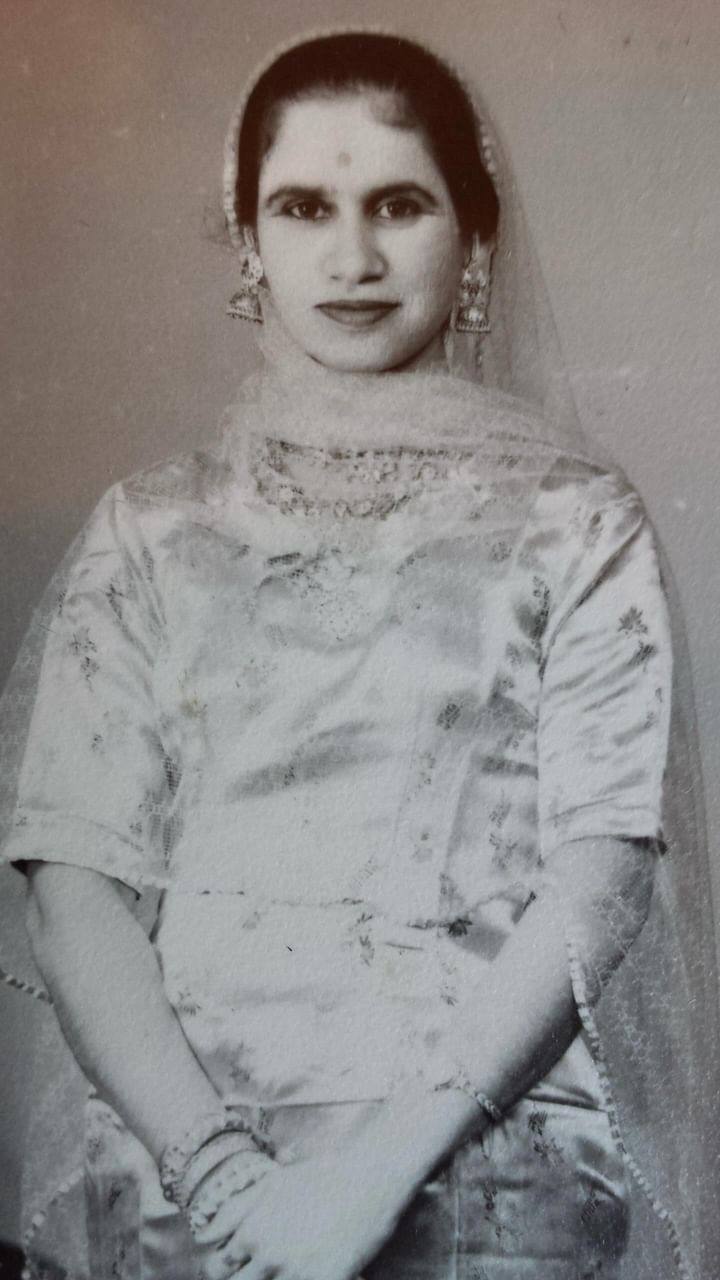

Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, while not a patient, played a significant role in visiting and supporting the troops. His visits to the hospital were a morale booster for the wounded soldiers, reinforcing the bond between Indian royalty and their men.

The hospital’s administration ensured that the cultural and religious needs of the soldiers were met. Separate kitchens were established to prepare meals according to Hindu and Muslim dietary laws. Religious spaces were also created to allow soldiers to practice their faiths, with areas designated for prayers and ceremonies.

Nursing staff, both British and Indian, worked tirelessly to care for the wounded. The integration of Indian orderlies helped bridge language and cultural barriers, making the recuperation process smoother for the patients. The local community in Brighton showed great support and interest, with many residents volunteering to assist.

In recent years, the story of the Royal Pavilion’s transformation into a military hospital has gained recognition and is now an integral part of the narrative of Brighton’s rich history. It serves as a reminder of the global dimensions of the First World War and the enduring bonds forged between Britain and India during those years.

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →

South Asian Heritage Month dates changed to "July" from 2026 — Learn more here →